Is Your Dog Desensitized to Your Commands?

There’s another kind of desensitizing that people do that’s not so good. In fact it’s downright harmful. And the worst part is that we usually don’t even realize we’ve done it. We desensitize our dogs to our commands and cues. This makes both hunting and training harder, because we’ve created a situation where we now have to do way more than we should to get a response from our dogs.

The numerous ways we teach our dogs to not respond to our cues are, for the most part, linked together. One leads to another, which starts the snowball rolling downhill fast. The problem usually begins with repeating a verbal command. Say we try calling our dog in by saying, “Here!” but nothing happens. So we repeat the command.

Still no reaction from the dog, in fact, good old Spot looks our way and then meanders off on his own. Now we turn to shouting at full volume and with some serious frustration (and perhaps a few more colorful words) added to our voice. The neighbors hear you a quarter-mile away, and good old Spot finally decides he’d better quit what he’s doing and come to you. Or maybe he decides to go the opposite direction because he doesn’t want to deal with an angry person. This happens several times a day and has gotten to be standard practice and the dog’s house. And when your dog finally does come to you, it sure doesn’t look confident or happy about it, which is a reflection of the anger and frustration it’s gotten from its handler.

What just happened?

First of all, if the dog finally comes when you get to the third time or more and are yelling, you’ve taught it to count to three and wait for your loud voice. It knows exactly how many times it can ignore you before it finally has to give in and listen. Your dog also has learned that it only has to come when you shout at it at full volume; it’s become desensitized to anything but that routine.

Why did it happen?

The best answer is inconsistency on the part of the dog’s trainer. When the dog was learning to come, it was taught via handler inconsistency to ignore, or become desensitized to, quiet commands.

How do we fix it?

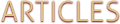

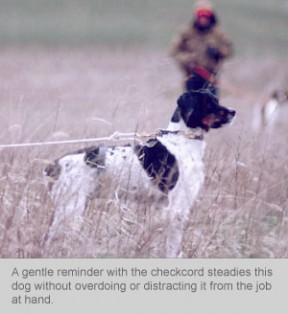

As with training in general, prevention is easier than a cure. To retain the dog after it has formed a behavior pattern will take many more repetitions than it would have had the dog initially been trained to respond to quiet cues. With any command, say it once in a firm and quiet voice, then enforce it. Do not repeat it while you’re enforcing it, as that leads to the while counting thing again. That’s one big reason we rarely use verbal commands in our training; we get the dog to do what we want, develop a patter of learned behavior, and then give the cue a name after the dog is doing it correctly and consistently. This means spending a lot of time on the checkcord and never verbally asking the dog to come unless you have the checkcord in your hand and can enforce the command. When the dog does come to you, quietly give your verbal command, but say it just one time.

"...most of the time, all the talking we do around our dogs is done more for our benefit than theirs."

Dogs aren’t born speaking English; most of the time, all the talking we do around our dogs is done more for our benefit than theirs. And when the voice is used constantly, it becomes background noise to the dogs, and they learn to ignore it. Again, we’ve desensitized them to our voice by using a lot of meaningless chatter. Have you ever been around a person who talks nonstop about nothing and you can’t get a word in edgewise? Think about not being that person around your dog.

Desensitizing is trained through more forms than just verbal commands, too. The physical cues we give can also be overdone to the point that the dogs disregard the first cue or wait for a stronger one because they’ve learned the first won’t be enforced. This is usually a result of the cue being increased so gradually that the dog has no reason to respond. Always start soft but if you need more, get your point across and then go right back down to a soft touch with your cues.

Don’t nag, either. It’s sort of like the radio in your car: When you’re on a long trip by yourself and you’ve got the radio or CD player on, the tendency is to gradually turn it up a little at a time because it sounds better and covers the road noise. Then you arrive your destination and shut the engine off without turning the volume back down, and when you get back in and start the engine, the radio is so loud it almost knocks you out of your seat. The volume was turned up so gradually you didn’t notice how loud it had become. Similarly, there are going to be times in training when you need to “turn up the volume” – turn it up fast to “loud” then go all the way back down to the softest cue. This teaches the dog to respond to a quiet cue because the loud one is unpleasant and is a correction rather than a normal cue. And you won’t desensitize your dog in the process.

When we use physical cues, whether it’s with our hands or body language, a lead, the checkcord, a whistle, or an e-collar, we need to start soft. If more is needed to make a correction, don’t increase the cue so gradually the dog doesn’t notice; instead, turn the “volume” up, and make your point, then go back to a quiet cue.

It’s easy to pick out a dog that has been desensitized. They typically do one of two things: act a bit fearful and look at their handler almost constantly, or ignore the handler and do whatever they want. The first come from being too controlling and heavy-handed; the second come from not enforcing commands after one cue.

A soft touch leaves the style in the dog, while a dog that has been dominated will still perform but will lack the confident and classy look of a dog trained with a lighter touch. The light-touch dog is trained; the dominated dog is broke. If we keep our commands to a minimum, we allow the dog to concentrate on doing its job rather than listening to us chatter. Over-handling turns a dog into a robot with no sense of independence, and robots don’t find many birds because they’re usually afraid to venture far enough from their handler for fear of a correction. A person who is over-controlling is usually a person who gets a dog “broke” but not trained. The dog is reacting more out of domination and fear instead of confidence in the lessons learned.

Believe it or not, it’s also possible to desensitize a dog to praise. Over-rewarding with effusive praise takes the dog’s focus off its job and desensitizes it to a gentle touch, while a light touch or quick pat on the shoulders tells the dog it has done well and also allows the dog to continue doing its job.

The end product of desensitizing is a dog that exhibits boredom, confusion, or fear (and fear includes bolting and running away). Slow down, take your time to teach the dog what you want, and don’t be in a hurry to name the commands. When you do name them, be consistent and quiet. Give a command once, and then back it up with a non-verbal correction.

Less is more. Train and handle your dog with that short phrase in mind. Teach your dog to respond to a quiet cue the first time so you don’t desensitize it, and you’ll spend a lot more time hunting and a lot less time correcting.